How Old is ‘Haha’? The Sound of Medieval Laughter

A strange image and the earliest 'haha' in English.

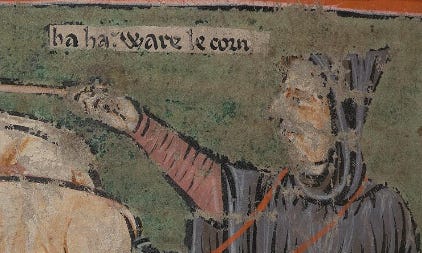

I was flipping through the digitised pages of a 13th century manuscript, when I stumbled across a very strange illustration. Well, the image itself – a shepherd wrangling his animals with a stick – isn’t that out-of-place in a bestiary. However, the caption of the illustration is unusual, or at least, striking:

‘ha ha; ware le corn’

(haha! beware of horns)

I stared at this note for a full minute. My Anglo-Norman is far from fluent, but there was no mistaking those two words. They can’t have meant ‘haha’ in the modern sense, could they? This sent me down a research rabbit hole that I’m not sure I will ever free myself from. How did medieval people laugh?

Laughter isn’t something commonly associated with the medieval period, which has gained an unfair association with dirt, plague and relentless misery. However, there’s lots of evidence that our medieval ancestors had a great sense of fun. The margins of manuscripts are littered with illustrations of people messing around in strange and fantastic ways (like the mad lad at the bottom of Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 264, f. 90v, who seems to be trying to fart a ball into a cup). Clearly, people were laughing—indeed, even the modern word laughter comes from the Old English hleahtor (hleh-ah-tor). This word is closer to modern English than it looks (for reasons too complicated and dull to tackle here, Old English has several ‘h’ consonant clusters - hl, hr, hw and hn - which gradually disappeared during the later medieval period. Often, removing this ‘h’ reveals the modern word: hraefn becomes raven, hring becomes ring).

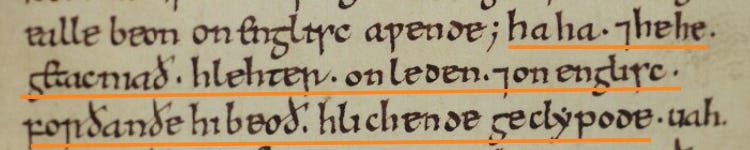

That’s all to say that the sound of Old English was very different to our modern language. It’s therefore remarkable that the earliest ‘haha’ in English comes from the Anglo-Saxon period. In the Grammar of Ælfric of Eynsham (a Latin textbook from the late 10th century), we find the following statement:

‘Haha 7 hehe getacniað hlehter on leden 7 on englisc, forðan ðe hi beoð hlichende geclypode’ (Haha & hehe signify laughter in Latin & in English, because they’re exclaimed [while] laughing).1

Surviving in multiple copies, Ælfric’s work is not only the oldest Latin grammar written in English (or, indeed, any vernacular language), but it’s also been described as ‘one of the most popular texts of eleventh- and twelfth-century England’.2 Truly, it was the Twilight of its day. The textbook is full of fascinating insights into the way language was conceptualised in the late Anglo-Saxon period (helpfully, to describe how Latin is constructed, Ælfric often describes how its concepts apply to English). In Ælfric’s description of interjections, of which haha is a part, Jacob Holson asserts that we find ‘the only theoretical discussion of emotions in any Old English text’.3 Whether this is the only example is debatable, but Holson is correct that emotion, and therefore humour, tends to go unsaid in early medieval works. Think of Riddle 44 in the 10th century Exeter Book:

A wondrous thing hangs by a man’s thigh,

under its lord’s clothing. In front there is a hole.

It stands stiff and hard. It has a good home.

When the servant raises his own garment

up over his knee, he wants to greet

with his dangling head that well-known hole,

of equal length, which he has often filled before.4

The answer is a key, but the text purposefully leads its reader to a different (more risqué) conclusion. Whether you read it to yourself or to someone else, the humour translates: a thousand years later, it’s still funny to imply someone’s perverse for stating the obvious solution. D. K. Smith states that ‘the riddler’s success, and the resulting laughter, rests on the potential for shame and embarrassment – the chance to catch his victims with their imaginative pants down’.5 This is a good point, though it epitomises the issue with studies of medieval humour: emotion occurs away from the page. The joke may have come down to us, preserved as an illustration or riddle, but the reaction it invoked happened over a thousand years ago. The laughter is long gone.

Given the scarcity of other sources, Ælfric’s ‘haha’ becomes even more fascinating. Not only does he record ‘haha’, but he adds the variant ‘hehe’, which are both still used today. It’s remarkable that the spelling of these interjections hasn’t changed, though the pronunciation would have been slightly different. I touched on it briefly, but Old English is very different to modern English. Not only are there the ‘h’ consonant clusters, which add a sort of ‘breathiness’ to certain words (this isn’t technical at all, but words like hlāf – pronounced hlawf – begin with an aspirated intensity that just isn’t present in the hard ‘L’ of the modern word ‘loaf’), but the sounds of vowels also changed massively between the late medieval and early modern periods. As written, and assuming ‘standard’ late Old English pronunciation, we can assume that Ælfric’s ‘hehe’ would have sounded closer to ‘heh-heh’ than ‘hee-hee’. Of course, this wouldn’t change how people actually laughed, but it’s an interesting way to see how they imagined the sound of laughter. Is ‘haha’ a guffaw and ‘hehe’ a giggle?

In Middle English texts, it turns out that there are some fantastic descriptions of different kinds of laughter. Compared to the Old English sources, later medieval works are a laugh-a-minute. In Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale, we get the giggled ‘tehee’ as Alisoun plays a trick on Absolon, and in his Cook’s Prologue, we get another medieval ‘ha! ha!’.6 It’s actually rather embarrassingly prolific, even in texts that I’d read and which pre-date the 13th century illustration in Cambridge MS Kk.4.25. I blame the manuscript. When reading a text in a book, it’s easy to forget the age of the material you’re working with, as it’s been edited into submission and served to you in a lovely modern typeface. Despite its antiquity, ‘haha’ seems out-of-place when written above an unmistakably medieval image. The white banner gives it the look of a modern comic and, indeed, the words seem to be exclaimed by the shepherd as he watches the rams fight. It makes sense. It’s historically appropriate, and demonstrates that the illustrator was having a bit of a laugh. While it may not be the most obviously ‘funny’ image to a modern viewer, a sense of medieval humour - explicit and textual - survives.

Ælfric of Eynsham, Grammar, in St John's College MS 154, f. 138r (pictured).

Melinda J. Menzer, ‘Ælfric's English Grammar’, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 103.1 (2004), 106-124 (p. 106).

Jacob Holson, ‘Ælfric’s Interjections: Learning to Express Emotion in Late Anglo-Saxon England’, The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 69, No. 292, 815–831.

D. K Smith, ‘Humor in Hiding’ in Humour in Anglo-Saxon Literature, ed. by Jonathan Wilcox (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2000), 79-98 (p. 82).

Jonathan Wilcox also recently published Humour in Old English Literature: Communities of Laughter in Early Medieval England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2023), which almost certainly covers everything I did and more. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get access to it, even on JSTOR. If you have access and anything I wrote is incorrect, please let me know!

when I reply to a text with 'haha' I'll be thinking of this now!!

Lovely essay! It's so nice to think about humans and humour throughout history