Painting Horror on Faceless Faces: The artist of Chaldon's 13th-century fresco

What can we know about the mysterious painter of one of England's oldest Doom paintings?

The early 13th-century fresco in Chaldon Church is technically a Doom painting, a medieval mural of the Last Judgement. If you’re researching Dooms, the red-and-white painting is one of the first results Google provides. However, to describe the Chaldon fresco as just a Doom would be like describing the ceiling of the Sistine chapel as just a ‘Biblical scheme’.1 There’s simply so much more to say, and very few open-access sources that cite reliable research.2 It’s time to go analogue— let’s crack out the academic journals.

Chaldon is found in an area of South East England known the Surrey Hills. Articles about the village’s famous church always sound slightly bewildered by its remoteness. In 1885, J. G. Waller remarked that ‘the place is so retired, it is difficult to believe you are within twenty miles of London’, a statement that — even in the days of public transport — still rings true.3 Set within a stone’s throw of England’s busiest motorway, and just 19.1 miles south of Charing Cross, there are areas of Greater London more remote than Chaldon. Despite this, the cluster of houses remains a defiant piece of the countryside. The church is nestled in a maze of hedgerows and green fields, a little way from the village. It’s easy to find. When you reach the fork where Church and Ditch Lane diverge, a charming hand-painted sign points left: ‘TO THE CHURCH’.

The Chaldon Wall Painting

It’s difficult to articulate, but there’s a scent to medieval wall paintings. It’s not a bad smell, but a slight mustiness hits you when you open the doors to these churches, the odour of plaster that’s lingered in stone buildings for centuries. The mural is to the left as you enter. It’s beyond impressive; stretching as wide as the nave, the look of the white figures against their red background breathes antiquity. This simplicity and scale is not something we see too often in later paintings. However, its density of colour may be what ensured the mural’s survival.

From the Interregnum to the 1800s, there was no painting on the west wall of Chaldon Church. As is common for the period, it was covered in a thick layer of limewash from the 17th century onward. However, when decorators were stripping the plaster in 1869, Reverend Henry Shepherd noticed streaks of red showing through beneath. He was a clever man, Oxford-educated, and (as Waller notes) had been monitoring the process with an unusual level of care.4 Was he simply obsessive or did he suspect something would be found beneath the limewash? The work was called to a halt, and the Surrey Archaeological Society stepped in to preserve the painting. Unfortunately, it was too late to save the fragmentary scheme on the north wall, where the workers had stripped back the limewash to reveal a devil and two human figures, before promptly destroying them as well.5

At first glance, the painting is startlingly well-preserved for something that’s been encased in plaster. Its red ochre is vivid and the white figures are bright, almost cartoonish. In comparison to other roughly contemporary schemes (St Mary’s, Kempley comes to mind) it’s implausibly smooth and saturated. This is, of course, because it’s been heavily restored. The extent of the work is unclear. As the church website generously phrases it, ‘a certain amount of addition of [sic] colour was made’ in Victorian renovations, while the wax later applied to preserve it caused the lighter colours to fade.6 This is not uncommon. The Victorians had different standards for the restoration of medieval paintings, and often preferred to restore them to full colour rather than to preserve the original pigment. Think of the fantastic Doom of St Thomas’, Salisbury, where the restorer has corrected to such an extent that the form of the original painting is unclear. The cultural difference between our restoration culture and that of our great-grandparents is stark. As a general rule, if you’re viewing a painting discovered in the 1800s, you’re viewing it through the paintbrush of its restorer.

While researching this article, I found a drawing in the Surrey Archaeological collections which clarifies what the painting would have looked like soon after its Victorian restoration.7 Here, we can see touches of yellow ochre which have now been lost, as well as a dilute wash of pink that adds shadow to the inside of cloaks, the heavens and the skin of certain demons. Even from several meters away, the scene ripples with constant movement. In the centre, tiny human figures scramble up and down the ‘ladder of salvation’, a rare but self-explanatory metaphor for the movement of souls between Heaven and Hell. Around the ladder, countless scenes play out, forming countless moments that the casual observer could miss. Staring at the fresco on a cold morning in mid-November, I saw far less than I see now, looking back at the photos I took.

Seeing the fresco for the first time reminded me of J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country, a book about a WWI veteran who restores a medieval wall painting over the course of a languid summer. I don’t think any book expresses so clearly the feeling of seeing ancient art in the wild, unmoved and almost unchanged by the passing of time.

Here I was, face to face with a nameless painter reaching from the dark to show me what he could do, saying to me as clear as any words, 'If any part of me survives from time's corruption, let it be this. For this was the sort of man I was.’

What survives of an artist if only a shadow of his work remains? In later frescoes, we can draw information from schools and styles, but there’s nothing quite like the Chaldon painting. Flecks of red paint have been discovered in local churches, providing a tantalising hint of a more widespread tradition, but no survivals are complete enough to know for sure. As I stood before the fresco, my mind wandered to the travelling medieval painters I’d learnt about while living in the South West. The South East is still a stranger to me, its flint churches ugly to eyes trained on smooth sandstone. Had the artist been a local? What sort of man stood here nine hundred years before me, sketching out his image of Hell?8

The Chaldon Painter

Even if he was a local, this was no small-time country painter. The scheme at Chaldon is not only well-executed, but references literature from a variety of cultural contexts. Firstly, Waller notes that the ‘ladder of salvation’ scheme is unusual for an English church, more closely reflecting the archetype described in an 18th-century painter’s manual from Mount Athos. Separated by hundreds of years and thousands of miles, the mural at Chaldon fits it strangely well:

‘A monastery. A crowd of young and old monks outside the gate. In front a very great and high ladder, reaching to the sky. Monks are upon it, some starting to climb, others grasping the foot of the ladder, in order to rise higher. Above, winged angels appear to assist them. Higher still, in heaven, the Christ… Underneath the ladder a great crowd of winged demons seize the monks by their dress; they pull at some, but cannot cause them to fall. With others they have succeeded in drawing them a little way from the ladder, some with only one hand, others with two.... The all-devouring hell is beneath them, under the form of an enormous and terrible dragon.’9

Waller also draws comparisons between Chaldon’s imagery and the writings of Cæsarius von Heisterbach, a Cistercian monk active in the 12th and 13th centuries.10 Most notable of these allusions is the figure of the usurer in Hell, tormented by demons as money spews from his gaping mouth. Now, there’s a lot to say about this image, mostly due to its rampant antisemitism (an usurer is someone who lends money at interest, a practice forbidden in medieval Christianity).11 I’ll produce a scene-by-scene breakdown of the fresco in due course. However, many of the figures in Hell seem to find themselves reflected in Cæsarius’ Dialogue on Miracles. The passage describing the usurer goes like this:

In the diocese of Cologne a few years ago, a knight died named Theodoric, a very well-known usurer. At Taft falling sick, and matter going up to his brain, he went mad. As he was continually moving his teeth and mouth, his attendants said to him: “What are you eating, master?” He replied: “I am chewing money.” He had believed that devils were pouring money into his mouth.12

Cæsarius is an interesting source for this period of history. In the same text, he describes a Benedictine monk who ‘was a good painter, and so devoted to our Order, that refusing every reward but his bare expenses, he painted crucifixes of wonderful beauty over various altars in many of our monasteries.’13 This German monk is almost certainly not the Chaldon painter, but the account demonstrates the type of skilled labour he’d have performed, as well as the general educational background of these artists. Waller, with that iconic Victorian confidence, says 'there can be little doubt the artist was a monk, as none other could have received instruction in art, still less in the knowledge of the numerous “monkish” narratives which illustrate this picture’.14 This part of his argument holds water, as there would be few opportunities to learn these schemes elsewhere. However, Waller’s conclusion that ‘he may have belonged to the same order as Cæsarius’ is based on very little evidence.15 The current dating places the Chaldon mural several decades before Cæsarius wrote, though it seems the writer and painter were drawing their imagery from the same cultural reservoir. Whether that was Benedictine or Cistercian, or something else altogether, it’s impossible to say.

The Chaldon painting is a fresco, but not of the ‘true’ fresco technique found in Greece and Italy, where paint is applied to fresh, damp plaster. The technique popular in English churches was fresco-secco, literally ‘dry fresco’. The pigment had to be mixed with egg and oil before it was ready to be applied. The artist would have done this himself, tapping red and yellow ochre into the liquids and then sweeping the emulsified ‘tempera’ mixture over dry plaster.16 He was an experienced painter, and talented for his day. Working in dark paint on a light surface is not easy, and despite the painting’s excellent execution, there are a couple of places where he faltered or redrafted. On the far right, in a depiction of the Harrowing of Hell, the line of Jesus’ leg has been corrected (shown in the white square).

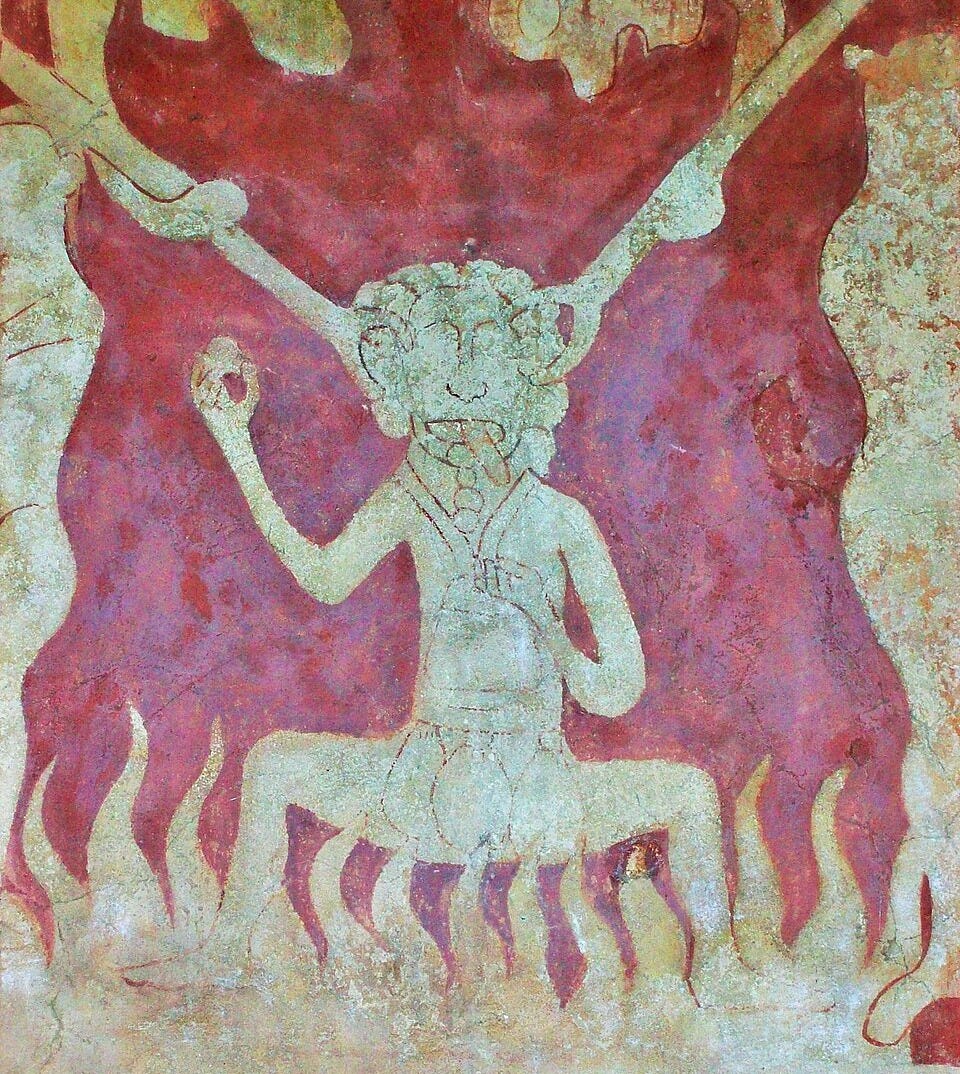

The composition of this vignette is interesting, and demonstrates many of the artist’s stylistic quirks. The figures are blocky and faceless, the limited details of their bodies rendered in thin red lines. Checking it against the Victorian copy, we can see that the flames would once have been yellow, and the inside of Jesus’ cloak would have been pink. There’s no record of the figures having faces, possibly to avoid the painting becoming too convoluted or hard to read at a distance. It doesn’t affect the impact of the scene; in fact, I think it heightens it.

Jesus stands on the bound devil like a hunter with a twelve-point stag, using its body as a barrier between his feet and the sharp teeth of the Hellmouth. This is the motif described in the Byzantine painter’s manual: ‘the all-devouring hell is beneath them, under the form of an enormous and terrible dragon’.17 In early medieval art and literature, Hell is often personified as a great monster, its entrance, a mouth full of sharp teeth. In Vercelli Homily 4, it’s explicitly said that:

‘Ne cumaþ þa næfre of þæra wyrma seaðe 7 of þæs dracan ceolan þe is Satan nemned. Þær æt his ceolan is þæt fyr gebet, þæt eall helle mægen on his wylme for þæs fyres hæto forweorðeð.’

(They [the damned] never come out of the pit of serpents or of the throat of the dragon that is called Satan. There at his throat is the fire stoked, so that in his torment all the host of Hell perish in the fire’s heat).

Vercelli Homilies, ed. by D. G. Scragg, p. 188, ll. 9-10

This is the same concept being depicted here. We can see the ‘throat of the dragon that is called Satan’, we can see the the fire stoked within. However, in this image, the damned are able to make it out of the fiery throat of the dragon. Faceless Jesus, having conquered the devil in a very literal heroic sense, bridges the mouth of Hell with its body, and the sinners ascend from the flames in gratitude. It’s often said that medieval artists struggled to represent pain, but I think the Chaldon painter understood something we forget if we view art as a relentless push for realism. Emotion and sensation are not just displayed on the face, but are manifest in the body. The repetition of the grasping figures in the flames, the way they clutch at Jesus’ outstretched hand, tells more of their suffering than a grimace.

It’s well-known that the Chaldon mural is one of the oldest and largest medieval wall paintings in the UK. I’m hesitant to throw around superlatives like ‘oldest’ because there are several other roughly-contemporary surviving schemes, as well as numerous fragments that have yet to be fully dated. In any case, many of these paintings have not been analysed in decades. Art and archaeology have made great technological leaps since the mid-twentieth century, and it would be interesting to see new analyses of these sites made with modern techniques. Chaldon’s mural is certainly one of the oldest in the country, but calling it ‘England’s oldest’ is a bit meaningless, as it’s unfalsifiable.

This is, of course, excluding Anne Marshall’s fantastic website Medieval Wall Painting in the English Parish Church. Nothing I write can compare.

J. G. Waller, ‘On a Painting Recently Discovered in Chaldon Church, Surrey’, Surrey Archaeological Collections, 5.1 (1871), 275-306 (p. 275). Available here.

J. G. Waller, ‘Recent Discoveries of Wall Paintings’, The Archaeological Journal, 30.1 (1873), 35 - 58 (p. 20). Available here.

I can’t find the source for the information on the north wall painting, but it is reported on the Chaldon Church website, which is otherwise very accurate.

Waller, ‘On a Painting Recently Discovered’, pp. 278-279.

K. F. N. Flynn, ‘The Mural Painting in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Chaldon, Surrey’, Surrey Archaeological Collections, 72.1 (1980), 127 – 156 (p. 151). Available here.

I note that stairs would also work, but the metaphor stands.

A. N. Didron, Christian iconography; or, The history of Christian art in the Middle Ages, trans. by Margaret Stokes (London: H. G. Bohn, 1881), p. 380.

I use male pronouns not because medieval women were not artists; many were, and their work decorates some of our most beautiful surviving manuscripts. However, I haven’t heard of a female monastic artist travelling from town to town in the manner of our 12th century wall painter. I would be delighted to be misinformed!

Given that this was forbidden for medieval Christians, the job was often taken by Jewish people, who had been invited to settle in England by William the Conqueror. The country’s economy needed moneylending, and thus needed moneylenders. However, increased cultural and economic tensions in the 13th century saw a rising resentment of the Jewish population, who were expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I. It is fascinating to me that the Christian sinners have no faces but the Jewish-coded one has the shadow of features, closer to the demons than to the humans.

Ditto, Chapter XXIV.

Waller, ‘Recent Discoveries of Wall Paintings’, p. 47.

Ditto, p. 47.

Info on pigments from Flynn, p. 144.

Didron, p. 380.

Wonderful read and super interesting! It’s always mystifying to ponder over the person who painted frescoes such as these. Anonymous artists leaving behind such beautiful pieces of art in inconspicuous parish churches.

Fascinating!